Their Souls Would Not Be Satisfied

Reading : An address by “King Janos Sigismund”

: An address by “King Janos Sigismund”

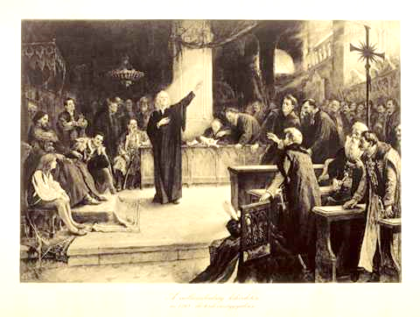

My new friend, Madame Preston, was going to tell you about this famous painting that is also printed in what you call the “order of service.” It depicts the Edict that I apparently made 450 years ago and includes many of my advisors and contemporaries. As I am here now and as I have just read the account of what happened after the Edict, Madame Preston was gracious enough to let me explain this image and the account of what follows.

First, though, I must correct something. The figure at the center of the painting is my dear friend and spiritual guide, Dávid Ferenc, enumerating the legal foundation for the Edict I will soon make. The figure sitting in a throne in the left-hand side of the image is supposed to me but the artist did not capture my true essence. This error is proven by history. In a letter, Giovanandrea Gromo described me as, “medium height and slender, with blond, silky hair and extremely fine, white skin. … [H]is blue eyes gaze mildly and with benevolence … His arms and hands are long and finely articulated, but powerful…” Anyway, I digress…

Dávid Ferenc became the preacher at my court through his relationship with my physician, Georgio Blandrata, standing to the side of my throne in the painting. Dear Georgio, a faithful man and a scholar whose prayer and study revealed that Jesus is not part of a holy trinity, sought to bring the Lutherans and the Calvinists in my realm into harmony, but failed.

The good doctor Blandrata and Dávid Ferenc taught me the truth about the great Rabbi of Nazareth. Such theological study was not new. I have explored questions of the spirit all my life.

I thank my mother, Isabella – may her legacy be blessed – for bringing me before humanist scholars in my boyhood. People say she was the most educated woman of her day and she shared her love of learning with me. When she ruled our kingdom, Mother insisted that people of different understandings of the gospel live together in peace. In the future, people will say that Dávid Ferenc proclaimed that “we need not think alike to love alike.” These words never did escape his lips but this philosophy guided Mother’s rule and mine and inspired me to make the Edict in Torda.

I did not live long after I made the Edict. Your woman priest, Heather, tells me she heard I died in an unusual carriage accident. But someone else told her it was a simple fall from my steed. And other accounts describe me as “gravely ill” at the end of my life. How I was received into the hands of death, I don’t know but I do know I died in 1571.

I had bequeathed my realm to a man in whose mind and faith I could trust but he was forced out of the kingdom. The land I once ruled then fell into the hands of Bathory Istvan, a papist, who rescinded my Edict. You can see him sitting to my right in the painting. The churches once seized by believers in the unity of god fell back into Catholic hands. The Unitarian faithful were then forced by Bathory’s armies to proclaim belief in the Trinity.

Even so, the good Dávid Ferenc would not submit, would not stop proclaiming the truth about Jesus’s nature. For his courage, Dávid was sent to prison in Deva, where he died in 1579, his body interred in a grave without a stone, like a common cur. History tells us that he wrote these words on the wall of his cell, making them his final testament:

Nor lightening, nor cross, nor sword of the Pope,

nor death’s visible face,

No power whatever can stay the progress of Truth.

What I have felt I have written, with faithful heart

I have spoken.

After my death the dogmas of untruth shall fall.

If this is a community of Unitarian believers, gathered long after our deaths, then I know the truth Dávid Ferenc taught me, the truth he died for, is still alive, is still proclaimed, even here in this kingdom of Massachusetts. I grieve that my wise teacher and dear friend suffered as he did but celebrate that his suffering was not in vain.

This painting captures a moment that changed the world I lived in. The history that follows tells us that sometimes truth only prevails for a moment and is lost in the pursuit of power and idolatry. I pray that we never forget – that you do not forget, 450 years after that holy moment – that, as dear Ferenc wrote, “no power whatever can stay the progress of Truth.” I pray that you also remember that, as his imprisonment makes clear, the progress of truth requires our vigilance, our commitment perhaps even our very lives themselves to survive passage across the generations.

Who among you is afraid to practice their faith? How are questions of the spirit welcomed into public discourse? You call my Edict the Edict of Tolerance. Where must tolerance dwell so all souls and all lands may be at peace?

“Their Souls Would Not Be Satisfied: Torda 450”

The Rev. Heather Janules

First, I would like to thank Lee Barton for assisting King Janos Sigismund in slipping through a wrinkle in the time/space continuum.

As we just heard Janos Sigismund’s story of the Edict of Torda, I share mine, a story I also call, “a tale of three dinners.”

This past July, three Winchester Unitarian Society members – Mary Saudade, Cynthia Randall and I – took a journey to the birthplace of religious freedom. On our way to visit our Partner Church in Marosvasarhely, we stayed for a few days in Budapest, being tourists. Then we woke early, had breakfast and met our guide, John Dale, who led us into his car for the long trip to Transylvania. As I watched the landscape blurring by my car window, the urban summer heat of Budapest gave way to small villages and long stretches of farm land and forests. We were lucky to be in this region when the many fields of sunflowers were in full bloom, horizons streaked bright yellow as we drove through.

After easy passage across the border between Hungary and Romania, the view outside our windows shifted again to small towns and suburbs and finally our destination for the evening, Cluj – or Kolosvar, in Hungarian; the streets lined with ancient buildings and Communist-era, cement high rises. We checked in to that evening’s hotel and rested until it was time to walk to dinner.

Kolosvar is a city with many universities, giving the streets a youthful, “Harvard Square vibe.” Our walk concluded when we arrived at the 1568 Bistro. John Dale explained that the Bistro is in a building owned by Unitarian headquarters, rented out to help fund the denomination.

Travel fatigued, I didn’t first realize that 1568 did not refer to the street address but to the year of the Edict of Torda. When our charming waiter handed me an English menu, the connection became clear. On the cover was printed:

Inspired by Transylvania’s colorful cultural background we have created a contemporary cuisine incorporating new directions, new tastes. We are inviting you on this journey of discovery…The year 1568, as a symbol of religious freedom, inspired us to discover the perception of freedom in a culinary context…

My fatigue also moved me to think of a tagline for this restaurant: “Religious freedom – It’s what’s for dinner!” However, I was impressed that the restaurant integrated this little bit of religious education into the day-to-day operations of their business. And the food was excellent. And I enjoyed getting to know our waiter, an engaging ambassador from the young adult community of Cluj to four tired and hungry Americans.

The next day, we toured the headquarters, adjacent to a Unitarian high school and church. I thought of all the middle-school Unitarian Universalist youth groups who come to Boston to visit what my friend calls “the stations of the chalice,” the many sites reflecting UU history. Now we were making such a pilgrimage, only connecting deeper to the historic root. Our walk through the church included seeing a large stone that Dávid Ferenc allegedly stood on to convert the masses, what seminarian students sometimes call “the holy potato.”

Kolosvar is the center of the Hungarian Unitarian Church, not Torda, as, after the Edict, this large city was where anti-trinitarians claimed their new-found freedom and became organized. Their efforts led to creation of hundreds of Unitarian churches before Sigismund’s death and the political shift that rendered them vulnerable to persecution.

After Kolosvar, Cynthia, Mary and I connected with members of our Partner Church in Marosvasarhely, receiving their gracious hospitality and touring many places of interest in the region – the Teleki Library, home of one of the original copies of the United States Declaration of Independence; the hat museum in Korispatak; pottery shops in Korond and so many Unitarian churches I lost track. Somewhere in our road tour of Unitarian Transylvania, our hosts asked if we wanted to visit Torda as it was somewhat on the way to our primary destination.

The site where King Sigismund made his Edict is now a large Catholic church. When we entered, it was almost empty, but for a few people quietly praying in the pews. We walked the dark red aisles and took in the stained glass, statues and architecture, finally discovering a few marble plaques in a corner, printed in three languages, acknowledging this as the place where the Diet of Torda gathered.

But even more interesting was viewing Aladar Korosfoi-Kriesch’s painting of the Edict, housed in the City Museum a short distance from the church. We arrived shortly before the museum opened but Laci, minister of our Partner Church, was not worried. He knew one of the tour guides and, besides, Laci told us, “the guide is Unitarian.” As always, it is good to have connections.

I had seen reprints of this painting in so many Unitarian Universalist buildings it was exciting to see the original, sort of like seeing the Mona Lisa in person but with much less security.

As we pause to observe the 450th anniversary of Torda, I find meaning in both the civic and spiritual significance of Sigismund’s Edict. As a United States citizen, I now realize how much I take freedom of religion for granted. Unitarian Universalist historian Susan Ritchie affirms there is no direct influence between the Edict and the US Founding Fathers.[1] Yet, the authors of the US Constitution were inspired by the Enlightenment, by ideas imported from Europe. As Lev Lafayette observes in a sermon, the legacy of the Edict of Torda is, “the idea of national unity built on principles of freedom and reason, rather than ethnicity. This idea would be repeated in both the French and American revolutions and they remain the core principles by which one judges whether a society is modern, secular and democratic.”[2]

The spiritual meaning for me comes through how Dávid Ferenc exemplifies what it means to be Unitarian Universalist. As I recently affirmed with a family who sought the Winchester Unitarian Society for a memorial service for their mother, a woman who fled Nazi Germany as a child and explored a number of spiritual traditions throughout her life, what makes someone a Unitarian Universalist is not the content of their religious conclusions but more that they are forever asking questions and forever open to new insights and communion with the divine.

We see such spiritual curiosity in Dávid Ferenc, who, like many here today, went on his own “journey of discovery.” Dávid was raised Catholic, converted to Lutheranism and then became a Calvinist before identifying as Unitarian. Dávid’s approach to faith as a “living tradition” likely came from many influences. As Joseph Ferencz and John Szasz name in a lecture, Dávid had a renaissance world view that was, “dynamic, tending toward the natural and toward harmony; he is a follower of evolution, even in the development of religious life.”[3] Influenced by studying in Wittenberg and connecting with Italian humanists and Polish anti-trinitarians, Dávid’s ethos of spiritual inquiry echoed the rich and eclectic early education of Sigismund.

I also see a clear connection between Dávid’s belief in the primacy of conscience and contemporary Unitarian Universalist identity. The Edict of Torda not only preserves the civil rights of diverse believers but names spiritual integrity as a value and cause to protect freedom of the pulpit. As the Edict affirms of preachers, “no one shall compel them for their souls would not be satisfied.”

Dávid understood spiritual belief as a truth beyond argument. As he wrote in a letter to a friend shortly after the Edict, “You are living in an age in which seeking for the truth and the open confession of our feelings is inadvisable. But those who are guided by the Soul of God may not keep silent. So great is the power of the soul that it will be triumphant, even if the whole world would be in rage or opposed to it.”[4] Similarly, I recall many who affirm they left another tradition and joined a Unitarian Universalist community simply because they could no longer recite creeds and sing hymns with spiritual ideas they do not believe in.

Here is where the second dinner comes in. Those who attended our Thanksgiving service remember we invited interfaith leaders to share something from their tradition that speaks of gratitude. One leader was Dr. Fehmida Chipty, a local Muslim.

As we began to prepare for worship that morning, Dr. Chipty asked me about Unitarian Universalism. I began by illustrating the faith from a historical perspective, affirming that Unitarians believe that Jesus was a human being. “So do we!” Dr. Chipty replied. This inspired a plan to meet sometime to share more about our traditions.

Later, over noodles and vegetables at China Sky, I explained that, while Unitarian Universalism is known for religious pluralism, it is not that you can “believe what you want.” It is more that one has the freedom to “believe what you must,” to believe what comes through exploring history and tradition, in conversation with life experiences over time, ever-knowing that new insights, new knowledge may always emerge and shape belief.

Dr. Chipty then shared some of the history of her branch of Shia Islam, Fatemi Dawat, a community that has recently experienced turmoil with the death of their previous leader and dispute about succession. The widely proclaimed leadership swiftly made changes in violation of long-standing values and practices. When Dr. Chipty refused to recognize this leadership, she and others who adhered to what they knew to be true about Fatemi Dawat and its genuine leader lost faith community, necessitating them to connect on-line, dispersed throughout the world.

As she concluded her story, I named my appreciation for her courage and the strength of her conscience. I affirmed that she “believes what she must.” I imagine that, had King Sigismund and Dávid Ferenc slipped through the time/space continuum and joined us at China Sky, they would concur that lest Dr. Chipty do anything else, her “soul would not be satisfied.”

It is ironic that this mealtime conversation began with two religious leaders making connections between Islam and Unitarianism as, a lecture by Susan Ritchie makes clear, proclamation of the Edict was likely influenced by Muslim thought and culture. Referring to the famous painting, Ritchie describes the image of Dávid: “While he speaks…a single ray of sun is shining directly on Dávid’s head. The clear implication is that God is directly planting the principle of toleration into Dávid’s brain. I call this the ‘Immaculate Conception theory’ of the Edict.”[5]

She continues with an argument that, due to the Ottoman empire’s approach of allowing conquered territories to practice their faiths and cultures uninterrupted and the political reality that Transylvania was then governed by Sigismund but technically under Ottoman rule, a strong ethos of religious freedom was present before the Edict. Ottoman authority over Transylvania inoculated it from some of the counter-Reformation campaigns, active and effective in nearby regions. Muslims and Christians of many kinds were already in close connection and relationship in communities of mutual influence.

The Hungarian Unitarian church denies a Muslim influence on the Edict, perhaps because the Turks are long-time political adversaries. It is difficult for us to prove a direct connection between Islam and the birth of institutional Unitarianism due to a lack of documents, existing documents written in Hungarian and Turkish and philosophical resistance from our Hungarian partners. However, Hungarian scholars seeking to discredit Unitarianism have found and made such connections.[6]

I conclude with the third dinner. It was the end of our stay in Transylvania and Mary, Cynthia, John, his wife Csilla and I sat down for supper on the outside patio of our hotel in Sighet. Our waiter came to the table and, to our great surprise, it was the same waiter who served us at the 1568 Bistro in Cluj, over a hundred miles away! Apparently, the restauranteur who rented space from the Unitarians did not pay their employees anything close to the hours they worked. It is unfortunate that Sigismund didn’t include something about labor relations in his Edict. So our waiter friend decided to return to his hometown and get a job there.

Remembering our pilgrimage to Transylvania, just as the 1568 Bistro drew on the symbolism of spiritual freedom to promote culinary fusion and innovation, the reappearing waiter also became a symbol to me, a symbol of how something – like religious liberty – can appear in different moments of time and space yet draw from the same human truth.

And the place of his reappearance, Sighet, well-known as the hometown of holocaust survivor Elie Weisel, reminds us of the importance of the human rights of all believers. Closer to home, we are also reminded by the Trump administration’s recent ban against Muslim immigrants to the United States.

The Edict of Torda in 1568, protecting people of different faiths from punishment and banishment, is sadly relevant and needed today, even in societies that claim to be, “modern, secular and democratic.” This is something to grieve and something to challenge as, in the words of Sigismund’s Edict, “faith is the gift of God.”

[1] Facebook conversation on “UUMA Colleagues” group. In response to an inquiry about whether we know that Thomas Jefferson was unfamiliar with the Edict of Torda by the contents of his library, Ritchie posted, “That is a piece of it. We can also trace the other direction- how awareness of the church in Eastern Europe did and mainly did not spread. There is a two degrees of separation between Jefferson and Torda in terms of influence if you go through Locke.” January 11, 2018.

[2] http://www.levlafayette.com/node/199

[3] John Szasz, John and Ferencz, Joseph. “When Hungarian Unitarianism Was Born, The Proceedings of the Unitarian Historical Society, VOLUME XVII, Part I, 1973. Semline: Braintree, MA.57.

[4] Szasz and Ferencz, 62.

[5] Ritchie, Susan. “Children of the Same God: European Unitarianism in Creative Cultural Exchange with Ottoman Islam,” Lecture Two. Minns Lectures, 2009 First Church Boston; Wednesday April 22, 2009.

[6] Ibid.