A Look into Our Church’s Windows

Stained Glass Windows

(from Insights vol. 2, no. 4 December, 1980)

by Susan Keats

Allen Nevins once said of the need for oral history, “What memories man carries to oblivion, and how absolutely they are lost.” But the memories I uncovered just in speaking to three people about the history of our Winchester Unitarian Church windows will not be lost.

My education on stained glass windows has opened up a whole new world to me. I have learned some interesting new facts about the profession itself, and I have learned some history about the members of our church.

My first tour through the church was with Robert Storer, our minister emeritus who served the church for many years. The stories he told are descriptive and factual – both of the themes of the windows and the people who donated them. My second tour was made a short time later, with Sherman Russell, who has so much knowledge of the church stored in his memory. Sherman showed me where stained glass windows should be signed in the lower right hand corner, and that became the first important fact I learned about the art. After these two tours I was fascinated with the art form as well as the donors. By the time I spoke to Wilbur Herbert Burnham, nationally known designer of stained glass, I knew that Burnham windows had been a part of the history of the church since 1923. How many people have enjoyed the windows since then! Before that time there had been no stained glass windows although the building was built in 1899.

We tend to pass the windows every day and seldom realize the stories wrapped up in the scenes, or the time and skill required to make such works of art. One reason why the stained glass window is fascinating is the number of people involved in producing a memorial – the donor, the church rector, or committee, and the artist, and the person or family to whom the window is dedicated.

Mr. Burnham told me that the design is an art form first – the use of color and shape dependent upon the overall effect to be achieved. Sunlight plays a major part. Lighter colors are used on north exposures where there is the least direct light. Darker colors are used on the south side in order to tone the amount of glare coming into the room. Heavy texture of paint may be used to add detail, and is baked on. Sherman told me an interesting tale about the north window in the sanctuary. I seems that it was once a plain leaded glass window, and there had to be an awning over it to reduce the glare. When the stained glass was installed a form of paint was stippled on to the interior. This north window was finished in 1922 by Mr. Burnham’s father Wilbur Herbert Burnham, Sr. The window was given in memory of Adelina Blanchard Tayler Hawes (1837-1891) and Mary Mosely (1827-1897) by Martha Alger Moseley, wife of Frank Moseley of Everett Avenue.

Recently the Smithsonian Institution named the four outstanding glass artists in the country, and three of these come from Boston: Wilbur Herbert Burnham, Joseph C. Reynolds, and Charles J. Connick. Nichola D’Asanczo comes from Philadelphia. Our church is privileged to have works by two of these masters. The south window is a Reynolds window. It is signed “Reynolds and Rhonstock,” but not dated. This window was given by Susan R. Campbell in memory of her husband, James Latham Campbell (1848-1922), and his first wife, Catherine Porter (1845-1889).

The window in the chancel, above the choir, is also a Reynolds window, and was given in memory of James Herbert Dwinell by his wife, Alice Brimmer Dwinell, probably in the late 1920’s. J. Herbert Dwinell was a member of his father’s coffee firm of Dwinell, Wright & Co., Boston. He was the grandfather of James F. Dwinell, Jr., Chairman of Winchester Savings Bank, and of Frederick M. Ives, Jr., who can still remember being taken to church as a young boy by his grandmother who would sit and stare at the lovely window. This window comes to life in the afternoon when the sun lights up the brilliant ruby glass and it fairly glows.

The Symmes Room windows were donated at two separate times. The middle window is in memory of Alice Frances Symmes (1851-1922) who was a superintendent of the Sunday School. Gifts from school children, who earned the money themselves, paid for this window, which was completed around 1923. (This window is unsigned). The lancets on either side of the Symmes window were dedicated during the centennial year of the church, 1965-1966. The plaque below reads, “The upper panel in loving memory of Herbert Edwin Stone (1879-1950). Devoted husband and father. Given by his wife and daughter.” They were Florence Stone and Gretchen Stone Cook. The themes of these windows are Unitarian history, and aspects of the universe. These lancets are Burnham windows. He has signed them, but in an obscure place. Look for the signature next time you’re having coffee.

Other stained glass windows are in the Michelsen Room and Meyer Chapel. The stained glass windows panes in the Michelsen Room, again by Mr. Burnham, were installed in 1963 when the room was used as a Sunday School chapel. They were a gift of Grace Chamberlain, in memory of her husband Edward H. Chamberlain. The theme of these designs are children and nature.

Meyer Chapel was a gift of Mr. and Mrs. John C. Meyer, in 1930. Before that time this space was the original Metcalf Hall. The windows were given by Mr. And Mrs. Harold F. Meyer in 1949. Because they are interior – the two small windows on the side walls get their light from large spotlights installed outside the Chapel. The theme of these windows is the Beatitudes, and the window at the far end of the Chapel also has a religious theme. They were all designed by Wilbur Burnham.

My last discovery was the cloister windows. They were a gift of Mr. and Mrs. Arthur Kelley, in memory of their daughter, Dawn, who died in Okinawa while serving in the American Red Cross during World War II. What a wonderful way for the Kelleys to remember Dawn! The story behind these windows was told in the Boston Sunday Globe pictorial section, January 1947. I had the privilege of knowing Mrs. Kelley when we lived on Mystic Valley Parkway. She graced us with a lovely welcome gift of homemade chocolates, and became the Keats’ family’s favorite neighbor. Mrs. Kelley was one of the most colorful people I’ve ever met, and the windows dedicated to Dawn Kelley have even more meaning to me because I knew Mrs. Kelley.

Stained glass windows are an art form and tell a story. They provide memories for the families who have donated them, and they add permanently to the beauty and richness of the church. There are stained glass windows in every part of the church except the newest Sunday School wing. The dates of the window span over 60 years, and the themes are as diversified as the dates.

The Cloister Windows

Rev. Robert A. Storer

May 27, 1956

Let me say at the outset that I know it will not be possible for me to say all that I would like to about the windows in the cloister of the church this morning. There will not be time. I regret, also, that it is not possible for you to look at the windows as they are being described. The cloister, as some of you may not know, is the long vestibule leading to the parish hall wing of the church. Many of us have walked by these lovely windows week after week without taking the time to really look at them. I trust you will sit down some time on one of the benches and let these pictures fashioned in glass give you their wonderful message. They were designed an executed by a contemporary artist, Wilber Herbert Burnham.

It seems appropriate on Memorial Sunday to recall them to mind, insamuch as they commemorate a young woman from this parish, Dawn Kelley Bartlett, who died in Okinawa while in the service of her country. Dawn is a symbol of the boys and girls known to us who answered the call, and who both risked their lives and gave them for a cause in which they believed. It seems fitting, also, on this day to speak of these particular windows bearing the mark of the Red Cross, insamuch as we celebrate this year the 75th Anniversary of the founding of the American Red Cross.

If there is one word that can be used to describe the purpose and activity of this organization, it is the word “Samaritan”, which means for me a person who responds instinctively to the cry of another human being in need. Webster defines a Samaritan as one who is ready and generous in helping fellow beings in distress. We hear first of a Samaritan in Luke X, the familiar story of the man who came from the ancient city of Samaria in northern Palestine. The Samaritans and Jews were bitter enemies. They had been for centuries. And yet this alien from Samaria was the one man who went to the aid of the wounded Jew after his own countrymen had watched his suffering and then passed by on the other side of the road. The Red Cross worker today is a Samaritan who will not pass by, but who will go to the aid of every man, regardless or color, creed or nationality.

In the very first window, Jesus is shown at the home of Martha and Mary, the two sisters very unlike in disposition – Martha, the doer of deeds, the busy, active woman who strove for perfection and who was concerned for the comfort of the important visitor; Mary the thoughtful dreamer who spent her time at the side of Jesus listening to his words while his sister prepared his meal. Jesus called attention to the two expressions of human nature, thought and action, worship and service, both necessary for the good and useful life. This window appropriately commences the story of the Samaritan, suggesting that all good works must be motivated by the love of God for all his creatures.

This leads to the window portraying the Good Samaritan which I have already described for you. The third window is a depiction of a famous quotation from the Sermon on the Mount, one of the Beatitudes: “Blessed are the merciful, for they shall obtain mercy.” Mercy is one of the most wonderful words in the English language; that quality of human love which Shakespeare described as not strained, not watered down, in no way qualified, but extended to all mankind. This again exemplifies the work of the Red Cross, ready at all times to help those who fight one another, not taking sides, mercifully lifting up whoever has fallen. It is significant for us to remember that up to the time of Jesus the dominant note in religious law was retaliation, an eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth. Jewish law, for the most part, rested on just retribution. God was a God of vengeance. Jesus, however, would have no part of this concept of God, whom he called instead a loving, merciful, forgiving Father. He substituted the very difficult teaching, “Return good for evil, bless those who hurt you and despitefully use you.” We know that Jesus suited the action to his word when in his greatest agony, on the cross, he cried out in regard to his persecutors, “Father, forgive them, for they know not what they do.” This man has made it very difficult for us to be Christians, has he not?

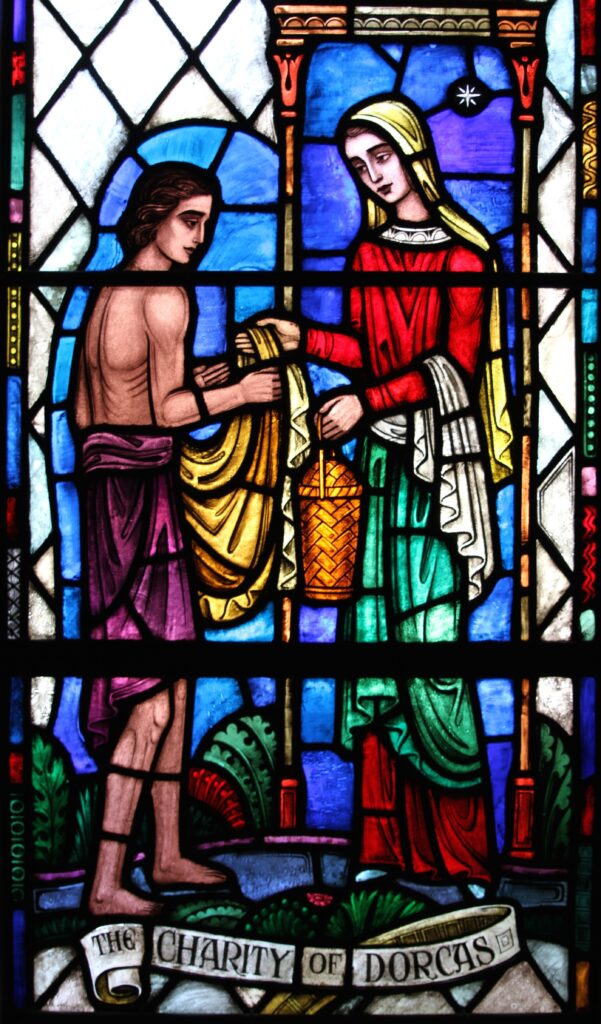

As we move on to the next picture, we discover a Christian woman by the name of Dorcas, described briefly in the New Testament as living in Joppa, an important seaside city, at the time Christianity as a new faith was spreading across the Mediterranean. The good book tells us specifically in six words that she was “full of good works and almsdeeds.” Dorcas symbolizes for us the kind of woman we know only too well in our own churches and in the community, unsung, unheralded, not mentioned in the papers, not a prominent clubwoman, but merely a doer of the word. We find her busy with a needle sewing for the church, the hospital or the visiting nurses, folding bandages for the Red Cross or working at the hospital, going from room to room, arranging flowers, reading and writing letters, running errands, smoothing pillows, saying the good word, sympathizing. We find her also on our streets, going to a neighbor’s door in time of trouble with something in her hands. These Dorcases of society, true Samaritans, deserve to be included in the message of the windows.

We move across the entrance doorway and find a window with the figure of Clara Barton, a woman of whom we can be justly proud. Reared in a Universalist home in Oxford, Massachusetts, she earned a reputation for herself at a time when it was felt that woman’s place was at home. Clara Barton was not content to remain where men and the scripture told her she should. When the Civil War broke out in this country, she was determined to organize a nursing service at the front. She made a trip through New England collecting money and donation, and gathering a force of lady helpers, among them Louisa May Alcott, Elizabeth Peabody, and Dorthea Dix. From then on she was found where women had not been found before, where the need and danger were the greatest, on the battlefield. At Fredericksburg, she went with the troops in the face of fire. “Follow the cannon” was her slogan. She became a legendary figure in the army. “Here comes the stormy petrel”, the solders would call to her as through wind and rain she made her way up to the front ranks. On one battlefield a man was killed in her arms; the bullet passed through her sleeve. She became known when she went to Washington to lodge a complaint against the officers who refused to turn over the elegant mansions of Fredericksburg to the wounded. She got what she wanted. Before long her name was mentioned with great respect. Shortly before his death, President Lincoln proposed that she be entrusted with the search for all wounded prisoners. Immediately after the war she went to the Confederate prisons identifying graves, tracing the missing, and organizing an information service. After that she travelled in Europe to regain her broken health. There, for the first time, she became acquainted with the work of the European Red Cross in the Franco-Prussian War. She wrote home: “When I saw the work of the Red Cross in the field, when I saw how much an efficient organization accomplished in four months, what we at home were unable to accomplish in four years; no needless suffering, cleanliness and comfort wherever the little flag made its way, a whole continent organized under the Red Cross, when I saw all this, took part in it, I said to myself, ‘If ever I return to my own country alive, I shall strive to make my people understand the Red Cross’.” She kept her promise. Through her efforts the American Red Cross was founded in Washington in 1881, 75 years ago.

Not willing to merely rest on her laurels, she thereafter went to the relief of the victims of the raging floods of the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers. She appeared in Florida to help fight yellow fever. She went to the Johnstown flood in 1889. In 1893 she was on the sea islands of South Carolina, where a hurricane had done terrific damage. At the time the grateful negroes named their girls “Clara Barton” and their boys “Red Cross”. She took care of the wounded after the blowing up of the “Maine” in Havana harbor. She was on hand after the tornado at Galveston. In fact, her name and her missions of mercy were bound up with every misfortune that swept the country during those years. The window is a worthy memorial to this Good Samaritan.

Next to Miss Barton in the cloister, but by no means a lesser figure, is the likeness of the Englishwoman, Florence Nightingale. Her life story is a sermon in itself. It is indeed a familiar one. I could not possible do it justice. Here was another woman who by her courage and determination, against the greatest of opposition, was able to recruit women for a war-nursing service for the first time in the history of Europe. While she was at the barracks hospital in the Crimea, the story of her work was being told at home, in court, in cottages, in tenements, in ale-houses, and on the streets. She belonged to the poor, to the illiterate, to the helpless. “The people love you,” someone wrote to her, “with a kind of passionate tenderness which goes to my heart.” In addition to “the lady with the lamp,” she was referred to as an “angel of mercy,” “the angel with the sweet approving smile,” “the star in the East,” “the shadow on the pillow,” and “the soldiers’ cheer.” Dr. Henry Dunant, a Swiss physician known as the founder of the Red Cross Society, had this to say about her: “Though I am known as the founder of the Red Cross and originator of the Geneva Convention of Nations, it is to an Englishwoman that all the honor of the convention is due. What inspired me to go to Italy during the war of 1859 was the work of this one woman in the Crimea.” In our cloister window, Miss Nightingale is seen as a nurse in the Crimea, still another Good Samaritan.

The next window bears simply the legend, “In memory of Dawn K. Bartlett, A.R.C. 1916 (the date of her birth), Okinawa 1945 (the year she died).” It is fitting that on this day we pay tribute to the memory of a daughter of this parish who with other young men and women volunteered to go to the battlefront of what I trust will be mankind’s last war. Dawn’s service to her fellow men has been described in many ways by friends and co-workers who knew her. Her family has permitted me to read letters written after her death. They are most moving. She was a girl who loved people and was greatly beloved by them, a friend of the enlisted man, a person who loved the unlovely as well as the lovely, another Samaritan. Dawn permitted her own health to be shattered because there was an important job to be done, and she worked inhuman hours doing it. At the time of her death, Basil O’Connor, then national president of the American Red Cross, wrote to her parents in part: “It is with deep regret that we received from the Casualty branch of the War Department the news of the death of your daughter Dawn in the southwest Pacific on December 25, 1945. We are proud to report that she endeared herself to her co-workers and that her services with the Red Cross and for her country were distinguished by conscientious performance of duty and selfless service on behalf of the members of the armed forces. Her life closed while engaged in a great service on foreign soil that is appreciated by her fellow Americans, by the military authorities and by the American Red Cross.”

Among her papers was a note from a lieutenant in the Fifth Marines who, at a port of embarkation, had seen Dawn as she left for overseas. In this note, which provides the theme for the final window, he wrote: “I came across something which I meant to let you have, nothing pretentious, just a few word which seem to go together well, which make me think of you and the things you have done. I rather think it will be one of the things you will carry around with you. It is from Dante, on the rendering of unconscious service in an unpretentious pilgrimage through life.” I shall read these words of Dante’s in conclusion, for they contain a thought for every one of us, every day of our lives.

“Thou travelest like one who goes by night,

Who carries a lamp behind him,

Which helps him not,

But those who follow are blessed by it.”

Are not these the right words with which to conclude out tribute both to the memory of those whom we have loved and lost, to the Red Cross, and to all Good Samaritans?